by Teri Ong

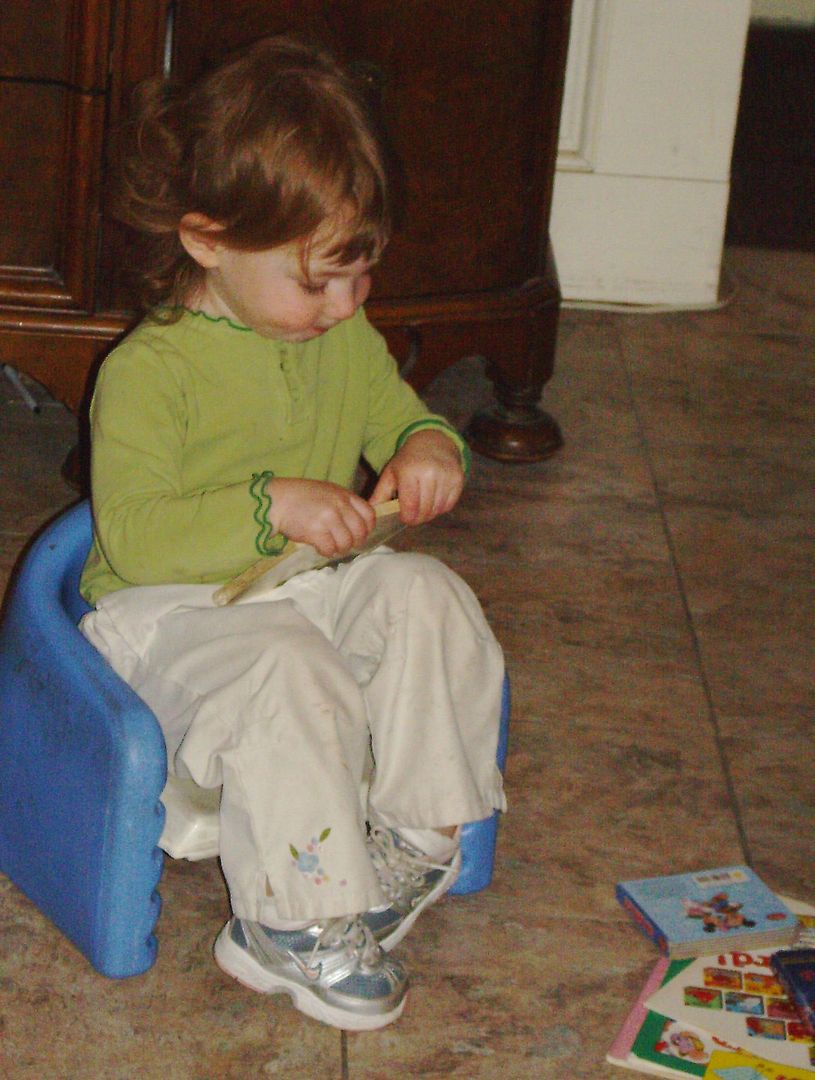

My granddaughter Faith, not quite two, is now becoming very interested in communication. She has a handful of words in her repertoire that are very clear to all – “Abi,” “dog,” “cat,” “book,” and, of course, “no”. Lately she has added “moo” to describe my ceramic cow creamer. But she cannot carry on a decent conversation with a grown-up using only those words, so she attempts to do so with her very own dear intonations.

My granddaughter Faith, not quite two, is now becoming very interested in communication. She has a handful of words in her repertoire that are very clear to all – “Abi,” “dog,” “cat,” “book,” and, of course, “no”. Lately she has added “moo” to describe my ceramic cow creamer. But she cannot carry on a decent conversation with a grown-up using only those words, so she attempts to do so with her very own dear intonations.

In an unbroken stream of sound, making use of the vowel sound “eh”, she sings forth her sentences in a series of melodious risings and fallings. When she occasionally pauses, she nods her head to indicate it is the listener’s turn to talk. If she is looking at a book, her melody will be punctuated periodically with “dog” or “cat” if there happens to be a picture of one.

In preparing my Introduction to Philology course this semester, I have refreshed my consideration of a number of abstruse ideas about language and language development. One that I came across a couple weeks ago is the idea that oral language is not neatly broken into words as they are in writing, yet we learn to recognize and use words orally in novel sentences long before we know anything about reading or writing a text. A wave pattern of a spoken sentence reveals an unbroken stream of sound, but we are capable between age two and three to break it into little bundles of meaning that allow us to make sense of the world around us and to communicate ideas back to those who populate it. What a miracle! What a sublime evidence of the imago dei.

I have always been intrigued by the sound of language to those who do not understand it. Gilbert Beers, who wrote a series of wonderful children’s books about the Muffin Family, described the confusing of language at the Tower of Babel. He said that someone asked a co-worker for some bricks, but it sounded more like “gobbly-gobbly-gobbly.” Then the co-worker answered back, “Why don’t you learn to talk?” But it sounded like “boogly-boogly-boogly.” I suppose my native lingo could sound very strange.

When I was a teenager, I saw a wonderful comedy routine done by Ricardo Montalban in which he acted out what American English sounds like to a non-English speaker from a Latin American country. The brilliance of his performance was that the audience could instantly recognize the flat, nasal, and gutteral aspects of English without them being in the right order to make real English words. Danny Kaye, likewise, had numerous comic routines in which he imitated the basic sounds of a variety of foreign languages.

My grandson We

sley a couple years ago was “reading” a poetry book. He could tell it was a book of poetry because the lines were arranged like poetry rather than like prose. So he “read” something that went (as best as I can recall)

Mugsy mugsy bugsy wump

Bumpy bumpy dumpy jump

Koomba doomba zoomba doo

Mimba dimba bimba boo!

His poetry bore no relationship to the real words on the page, but I was impressed that he understood that much poetry, especially poetry for children, has rhyme, rhythm and frequently, a good sized helping of nonsense words.

Even though I have been spending a great deal of time studying about words and reading words this semester, I have not had as much time as usual to write words. It isn’t that I haven’t had the desire; in fact, I have a lot of pent up desire. But other duties have pushed to the fore. The words are still there, just itching to be released.

So here they come! In honor of Wesley and Faith.

Mugsy, bugsy, tugsy, wump.

Here come words that want to jump,

Tigsy, togsy, tiggly tage,

Out of my mind and onto the page.

Jiggly, joggly, higgly pig,

Words that are little, words that are big,

Floggly, doggly, biggly bird,

Free at last to be seen and heard.

Musical, whimsical, choosical tune

Give me a pen, I’ll give you the moon.

Hippy, happy, finally fine,

Silly singing words of mine

.