By Teri Ong

I frequently see adds in Christian periodicals for the Harris brothers’ Christian youth conference called “Do Hard Things.” I appreciate very much the serious tone that they are trying to achieve with a generation of youngsters who have been raised in a wussy and silly culture. Most youth events are combinations in slightly varying percentages of kid foods (pizza or hotdogs), games, and raucous music. Adults know that those are not the things of which adult life should be made, but too many adults have more of a desire to “keep kids coming” than to “get kids going.” That is why I am glad the Harrises are doing what they are doing.

So what constitutes a “hard thing”?

It is tempting to think, as I did in my own youth, of dramatic ways of laying down our normal lives, ostensibly on behalf of the cause of Christ. I have known students who diligently studied Russian, Chinese, or Arabic so that they could minister in “closed” countries as soon as they were old enough to go. I have known students who gave up sleeping in beds so that they wouldn’t be too soft when it came time to sleep on the floor of the jungle somewhere. I even knew a brother and sister who went on highly restricted diets so they could empathize with hungry people in third world countries. I got my private pilot’s license when I was seventeen just in case I was called to minister in the bush country of northwest Ontario where I had spent time on summer missions trips. The worthy goals sometimes, however, get swamped in the emotional rush associated with the activity as it did for one young man we knew who was keen to go to  Africa on a missions trip because it would include climbing Mt. Kilamanjaro. He admitted to us that he was mostly interested in the excitement of his prospects.

Africa on a missions trip because it would include climbing Mt. Kilamanjaro. He admitted to us that he was mostly interested in the excitement of his prospects.

The problem is, as Alison Gopnik eloquently put it in “What’s Wrong with the Teenage Mind?”, “If you think of the teenage brain as a car, today’s adolescents acquire an accelerator a long time before they can steer and brake.” In other words, if we can get them up off the sofa or out of bed, they will pitch themselves headlong into a whole variety of activities that could cause damage to life and limb. Gopnik cites a Cornell University study that indicates that “adolescents aren’t reckless because they underestimate risks, but because they overestimate rewards– or rather, find rewards more rewarding than adults do… What teenagers want most of all are social rewards, especially the respect of their peers.” (C1, col. 4)

Gopnik further states,”…contemporary children have very little experience with the kinds of tasks they’ll have to perform as grown-ups. Children have increasingly little chance to practice even basic skills such as cooking and care-giving… The experience of trying to achieve a real goal in real time in the real world is increasingly delayed, and the growth of the [self-] control system depends on just those experiences.” (C2, col.2)

It seems to me, then, that the “hard things” that adolescents need to learn to do are the things that don’t given them a rush and that won’t necessarily elevate their status in the eyes of their peers. The “hard thing” is to NOT get the dyed mohawk in solidarity with the rest of the team. The “hard thing” is to wear your school uniform without complaining or pushing the boundaries of the rules. The “hard thing” is to sit with the adults in social situations and listen to them talk about adult life, even if you would rather be texting, tweeting, or otherwise twiddling your thumbs on an electronic device. The “hard thing” is to sit in the worship service with your parents rather than go off to the “teen challenge” in some other part of the building.

Does it help teenagers develop into serious-minded, responsible adults if they do these kinds of “hard things”? Gopnik writes, “…experience shapes the brain. People often think that if some ability is located in a particular part of the brain, that must mean that it’s ‘hard-wired’ and inflexible. But, in fact, the brain is so powerful precisely because it is sensitive to experience. It’s as true to say that our experience of controlling our impulses makes the prefrontal cortex develop as it is to say that prefrontal development makes us better at controlling our impulses. Our social and cultural life shapes our biology.” (C2,col.4)

With that in mind, here is a list of “hard things” that I am going to challenge the two remaining teenagers in my house to do.

Turn the lights out and go to sleep by midnight, preferably by eleven p.m., even if, and especially if you consider yourself to be a “night” person.

Get up after 8 ½ hours of good sleep.

Get dressed immediately and put some good food (spiritual and physical) in your system as quickly as possible.

Make your bed and tidy your room as quickly as possible. The hard part is not leaving it for “later.”

Get your assignments done as early in the week as possible. Don’t depend on the “last minute rush.”

Eat good foods regularly.

Turn off social media and unplug music when you are with “real” people.

Limit your game time to the amount of time it takes you to eat your lunch. (But don’t start dawdling over lunch so you can have more game time.)

Get exercise first by doing physical work– then find other ways to work out if you need to.

Cut out the procrastination factor on at least one item per day. For example, if you were going to empty your trash can tomorrow, do it today.

Sit down at the dinner table to eat your food.

Do at least one thing per day to make someone else’s life easier or more joyful.

I could make the list longer, but this will do for a start. These are the hard things that will make teenagers into responsible adults. Gopnik writes, “You get to be a good planner by making plans, implementing them, and seeing the results again and again. Expertise comes with experience.” (C2, col. 1) Oswald Chambers wrote that most of our life, adult as well as teenage, is spent in the mundane. It is in that valley that God batters us into the shape He wants us to be to do those other occasional hard things that we imagine for ourselves. That shape is called mature Christian character.

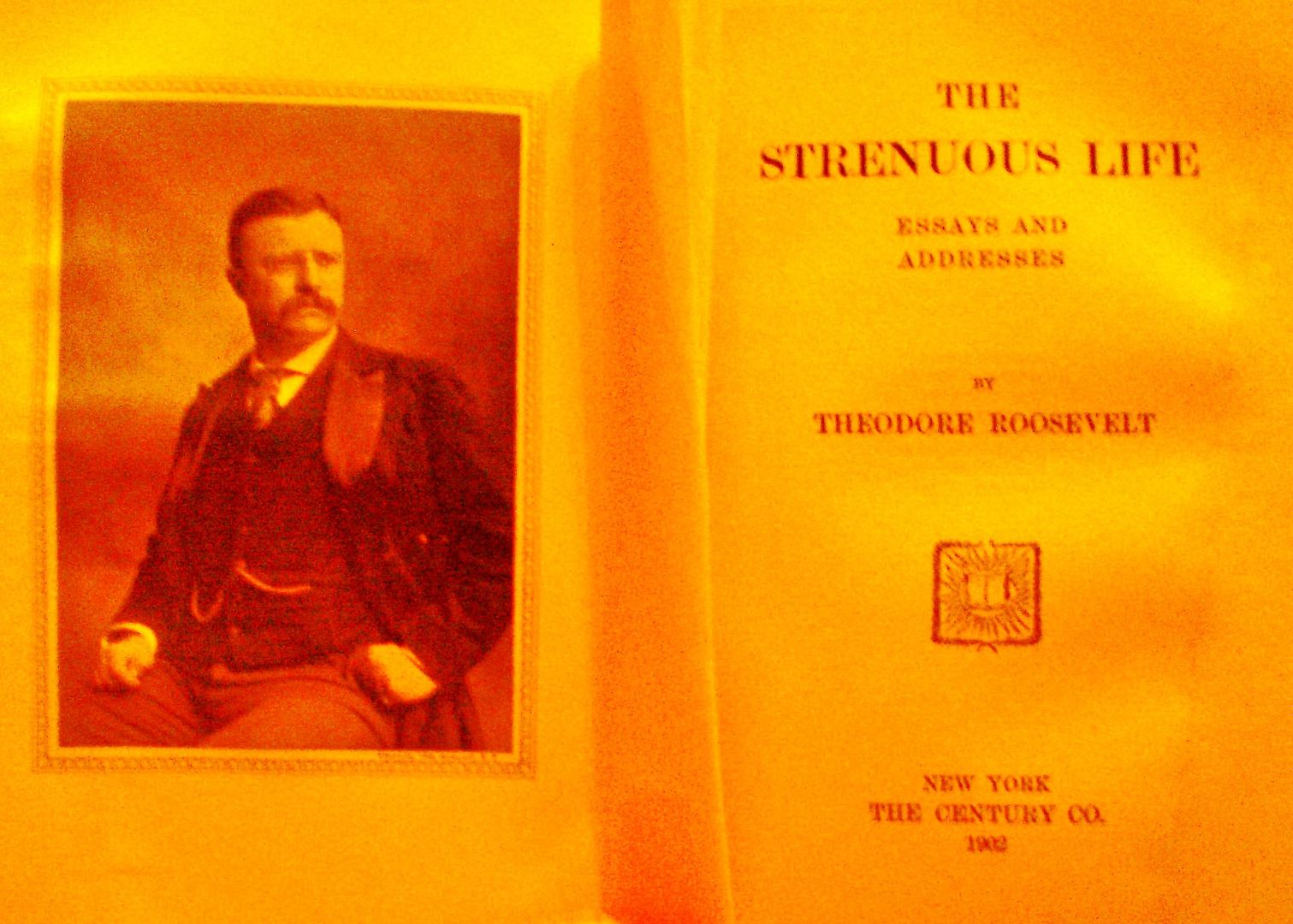

Teddy Roosevelt wrote brilliant letters to his sons, Kermit and Ted, on this very topic. I quote them here.

Dear Kermit:

White House, Oct. 4, 1903

Dear Ted:

Dear Ted:

The editor of these letters, Joseph Bucklin Bishop, said of them,

Teddy Roosevelt was a man who knew how to do hard things and how to encourage his sons by the pattern of his life to do them as well. The “pattern of good works” in which the Apostle Paul sought to instruct the younger man Titus could be summed up in one word – “sober-minded.” If you don’t believe me, read Titus 2:1-8. That is the single hard thing that is given to all in that passage– young and old, male and female. May we all work hard to achieve it.

References:

Bishop, Joseph Bucklin (ed.). Theodore Roosevelt’s Letters to His Children. New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1919.

Gopnik, Alison. “What’s Wrong with the Teenage Mind?” Wall Street Journal, January 28-29, 2012, C1-C2