by Teri Ong

In my last article, “In Defense of the Bible College,” I proposed that in light of new government regulations, church-based Bible colleges could well be the only way for students to get a college education which has not been defined and manipulated by our federal government. I based this on the premises that at the present moment state governments do not want to face law suits from trampling into First Amendment/church-state issues and that church-based colleges can practically operate without the entanglement of federal monies in the form of student grants and loan guarantees.

Dr. Kevin Bauder, president of Central Theological Seminary in Minneapolis, Minnesota, in his most recent article, “Federal Intervention in Higher Education,” raises a number of concerns which may even impact heretofore unregulated church-based Bible colleges. He writes:

Dr. Kevin Bauder, president of Central Theological Seminary in Minneapolis, Minnesota, in his most recent article, “Federal Intervention in Higher Education,” raises a number of concerns which may even impact heretofore unregulated church-based Bible colleges. He writes:

The largest problem, however, is simply the presence of federal intervention in an area that was previously private. In effect, the government is in the process of taking over a huge segment of American society. As this takeover progresses, it will be the federal government that determines who can teach and what will be taught at every college and seminary in America. The federal government will ultimately determine which institutions have the right to grant degrees and which will simply be shut down. [inthenickoftime@centralseminary.edu, Friday, Feb. 25, 2011, 2:10 p.m., paragraph 10]

Under the old system (since the 1990’s), colleges that wanted to be “accredited” had to apply for standing and pass a rigorous course of examinations and produce reams of “self-studies” to prove their legitimacy to an accrediting agency. That accrediting agency itself had to be approved by a higher up agency which essentially accredited the accrediting agencies. And since 2008, when the federal rules changed once again under the Obama administration, the ultimate approving agency is the federal government itself.

Bauder continues:

For Christian institutions, the implications of such a takeover are obvious. Christians have had to work doubly hard to gain a foothold in the private accreditation system. Once the feds are in control, accreditation is likely to become the wedge by which the government forces Christian colleges and seminaries to adopt policies that reflect prevailing notions on subjects like evolution and homosexuality. The potential for damage is both real and alarming. [ibid., paragraph 11]

Christian colleges have seen these problems coming for a long time, not just since 2008. As soon as the accreditors of accrediting agencies had to dance to the tune of federal regulators in the 90’s, many of our fellow institutions have faced the specter of philosophical and theological compromise in many forms, from the “politically correct” requirement to have a certain percentage of women on Bible college boards, to being required to hire faculty who would teach evolution (rather than creationism) in science courses or who would provide sexual diversity (perversity?) on staff. In the 1990’s and 2000’s, these battles were waged on a campus-by-campus basis. We know of a few colleges who stood their ground and won expensive legal battles to maintain accredited status in spite of their unpopular theological requirements. But there were scores more who caved to each new incursion into their freedom of conscience because they didn’t want to lose any of their “market share” of students by possibly being “unaccredited.”

How did we come to this cross-road? As Robert Sheffy, the great American revivalist in the late 19th century said, Christians rarely have things taken away from them; they usually give them up. Christian colleges essentially gave up their rights to operate according to freedom of religious conscience when we entered the accreditation fray in the first place. We must ask, why did we seek worldly credentialing of our institutions? I propose that we sought worldly credentials for these reasons:

1. We thought we could get the same intellectual respect as our worldly/secular counterparts by gaining secular approval of our programs.

2. We thought we could get a larger market share of students (and thus more money for our schools) if they could get access to federal grants and loans, and if they could transfer our credits and degrees into secular institutions.

Both of these are bad reasons– human prestige and money with strings attached.

We never should have tried to prove that our programs were “as good as” the big-boy secular programs. Our programs were “infinitely” better. We should have looked at secular standards as something to shun rather than as something to emulate. “The fool hath said in

heart, ‘there is no God.’” And that is precisely the position of the preponderance of those in control of federally approved and accredited secular institutions. That should make their degrees a mark of shame rather than one of credibility or prestige. After all, “ He who walks with wise men will be wise, But the companion of fools will be destroyed.” (Prov. 13:20 NKJV)

Instead of jumping through all their hoops and pressing ourselves into their molds, we should have stood up and said, “We know the GUT (grand unifying theory) of the universe that you are pretending to seek, and He is our Lord. By rejecting

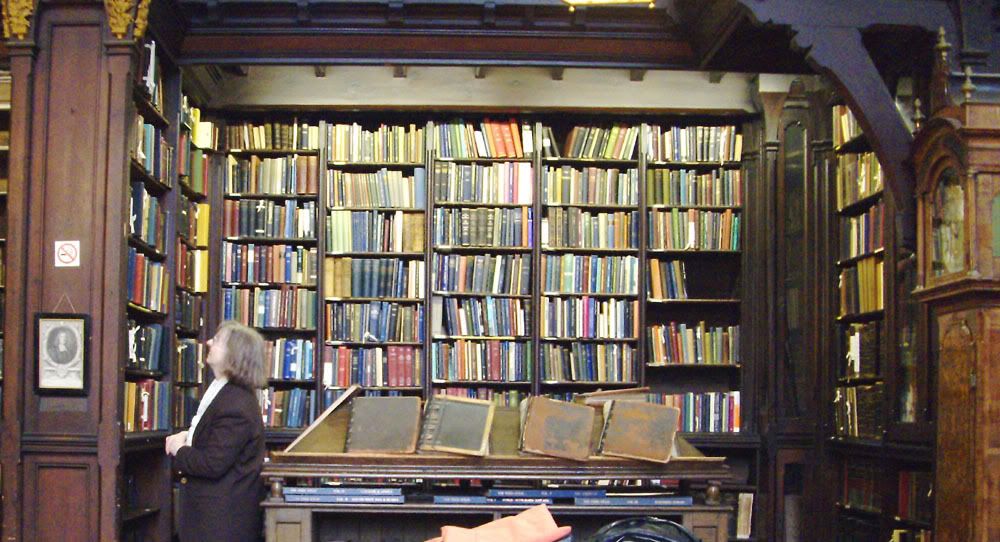

Dr. Williams’ Library in London, England Dedicated to the history of religious dissent

Him, you have rejected the basis of understanding the truth about that universe, past, present, and future.” We should have said to students who wanted to transfer secular credits into our programs, “We are sorry. Courses from that university or college failed to acknowledge the core truths essential to godly understanding and wisdom. We will not accept those credits.”

We should have told students, “Don’t go after federal grants and loans. If God wants you to study in this institution, He will provide the means for you to do so. It may be through good old-fashioned labor, it may be through the goodness of Christian benefactors who want to help you, but it should not be by going into debt to the government.” We might have been able to say those words if we had believed them ourselves– running our institutions by faith rather than by worldly business models and “financial planning” schemes.

Bauder continues:

The government is also going after unaccredited institutions. At the moment, the individual states recognize the right of colleges and seminaries to grant degree. In many states (Minnesota is one of them), religious institutions are completely exempt from the state’s oversight in this area. The Department of Education, however, is using its new leverage to pressure the states to force all degree-granting institutions to gain accreditation. In other words, if the federal government has its way, no unaccredited schools will be allowed to grant degrees. [ibid., paragraph 12]

The federal government may indeed strip us of the right to grant degrees for our programs, which ironically are frequently more rigorous and demanding than in secular institutions. [See Richard Arum and Josipa Roska, Academically Adrift: Limited Learning on College Campuses, Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2011 for an analysis of accredited programs] If that happens, Bauder suggests that we will have to find another educational model for training Christian students, especially students who are called to specialized ministry endeavors. He says, “Up to now, we have adopted a model borrowed from the medieval universities. We have coupled our educational process with the granting of degrees at the bachelor’s, master’s, and doctor’s level. That is just what we may not be able to do in the future.” [paragraph 14]

In that eventuality, I offer the following propositions:

1. Not receiving a “degree” does not hamper the receiving of an education.

For many centuries, at the medieval universities that Dr. Bauder references, women were not allowed to attend. In 1878 women were allowed to establish their own college in Oxford University, Lady Margaret Hall, but they were not allowed to grant degrees until 1920. That did not hinder them, however, from giving and getting a quality Oxford education.

The focus on transferability of credits and degrees has led to a destructive focus on institutional status rather than on the educating of individual students. Students have looked to their documentation to open doors to financial success and personal prestige rather than to their personal accrual and application of knowledge and skills. A return to “knowledge as its own reward” would purify the population of Christian students by helping them assess their true motives for pursuing higher education. A student who is seeking first the kingdom of God in his educational pursuits will have all things necessary added to him by God, regardless if, and perhaps especially if he rejects the lure of worldly prestige in the choosing. (Matthew 6:33) God has never punished any student for seeking Jim Elliot’s A.U.G. (Approved Unto God) degree.

2. The Biblical pattern of education is based on personal discipleship rather than on institutional prowess and prestige.

Christ gathered students around himself, not around a school. The School of the Prophets consisted of men who gathered around a man of God, such as Elijah or Elisha, to learn directly from him. Paul gained his high-level education by studying with the respected teacher Gamaliel.

In certain professional fields the question is not where you studied, but with whom. This is especially true in the arts. The resumes of concert musicians and serious artists are heavily weighted with the names of notable artists that taught and mentored that artist. I was much more impressed that my college violin instructor was trained by a man who was trained by the great Eugene Ysaye than I was by the fact that his training took place at Eastman Conservatory.

We must acknowledge that the principle of discipleship is at work in all fields of training to one degree or another. It could, and probably should become more important in Christian education once again. By way of example– not many people who read the works of Francis Schaeffer care much that he attended a small up-start seminary in its first year of operation. More people are affected by the personal influence of Gresham Machen and Cornelius VanTil in the young Schaeffer’s life which spills over into his later writings.

Oswald Chambers left the University of Edinburgh to attend a “one man show” in Dunoon, Scotland. He was a student in the home of Duncan MacGregor, a pastor who thought the institutional method of training pastors and missionaries was too much “factory” and not enough “garden.” MacGregor ran a Bible college out of his home in association with the Baptist church in Dunoon for many years. Chambers taught there for several years after his student days, and he also ran his own “Bible Training College” in London in later years. Chambers’ college was run along the same lines as MacGregor’s school. Chambers and his wife lived with the small group of students and they were all involved together in study, devotional and service pursuits, and the practical chores of daily living. When the college closed during World War I, Chambers and a number of his students went as a group to minister to British troops in Egypt because they had been knit into a functioning body by their time studying together. [See Abandoned to God, by David McCasland, Grand Rapids: Discovery House, 2000]

3. Qualification for professional jobs is not solely measured by certain degrees from certain institutions.

Everyone understands that not every student is equally adept and that not every institution does as good a job preparing students to perform well in highly specialized and technical fields. For example, it doesn’t matter if you have a degree from Harvard Law School or if you have carried out an efficient program of self-study, you can practice law in California if you can pass the rigorous California Bar Examination. It doesn’t matter if you have a medical degree from Johns Hopkins or the University of North Dakota– you still have to complete numerous internships and pass state board exams to be able to practice medicine.

C.P.A.’s and certified financial planners to electricians, plumbers, and even beauticians have to pass comprehensive examinations to prove that they really know what they were ostensibly taught in their various institutional programs, no matter what “degree” or certification they received. Pastors and missionaries usually undergo examination by ordination councils and mission agencies to confirm their qualifications.

If Bible colleges and seminaries are stripped of the right to grant degrees, they may still have a key role in developing comprehensive examinations in various specialties such as Bible exposition, theology, church history, Biblical languages, pastoral ministry, Christian education etc. Students who pass their examinations could receive designations such as Theology Scholar, Biblical Languages Scholar, etc. Students could spend as much time as they needed “studying to the test” with teachers to guide them and take the applicable exam whenever they were ready.

Such a system is closer to the Oxford-Cambridge model than it is to the present-day American system. At Oxford and Cambridge students “read” in their field and write essays that are discussed and critiqued with a tutor. After three years of guided study, they take a comprehensive exam in their given field. They either pass or they fail. There is no transcript of courses or grades accumulated over numerous semesters; they must prove they know what they set out to learn in order to get a “first” ranking as a scholar in their particular field.

The tutorial style of instruction is historically tried and true, and is easily adapted to a more personal discipleship model of Christian education. We have been using a modified tutorial style at Chambers College since 1999. Years of study followed by a comprehensive examination would eliminate the need to conduct courses in a way that must fit into the narrow definitions of the federal regulations concerning “credit hours.”

Non-traditional credentials such as I have described, though not meaningful in the secular world, would come to have meaning in churches and other religious institutions served by various Bible colleges and seminaries. Our colleges and seminaries have offered non-traditional degrees such as the Th.D. and D. Min. for some time.

4. Christian education, including higher education for the preparation of pastors and teachers, must take place in some form as long as the church of Jesus Christ is on this earth.

The teaching of new believers by those who are more mature in the Christian faith is the very heart of the Great Commission. (Matt. 28:20) Are we surprised that the enemy of Christ will use anything, including the federal government, to stymie and thwart effective forms of Christian preparation and scholarship? Jesus said, “…I have chosen you out of the world, therefore the world hates you.” (John 15:19) Those in the world will never look on Christian education as having any significance, no matter how many of their hoops we jump through. The Apostle Paul observed that what we have by way of knowledge and wisdom from God will never be good enough in the eyes of the world: “For Jews request a sign, and Greeks seek after wisdom; but we preach Christ crucified, to the Jews a stumbling block and to the Greeks foolishness, but to those who are called, both Jews and Greeks, Christ the power of God and the wisdom of God.” (I Cor. 1:22-24)

If our ability to grant the degrees which have been under the purview of religious institutions of higher learning for over a thousand years is suddenly taken from us, it must not stop us from doing what God has called us to do – train faithful men (and women) who will be able to teach others also. (II Tim. 2:2) If we are forbidden to convene formal classes for high level instruction, we will need to take a stand with Peter and “obey God rather than men.” (Acts 5:29) What is the difference between a qualified instructor teaching a course on the Greek exegesis of the book of James and a pastor preaching through the book expositorily for his congregation on Sundays? Both are carrying out their God-given duty to teach disciples. How can you stop one without stopping the other?

From the 1660’s until the early 1800’s, students who dissented from the Church of England were not allowed to attend Oxford or Cambridge. How were Baptist, Congregational, Presbyterian and Methodist preachers to be trained when they could not study in the institutions which had produced the likes of an Owen, Perkins, Ames and other notable Puritan divines? They had to study in small “dissenters academies” which often had to move from place to place to escape official sanction. Yet these dissenters academies were the place where true educational innovation and effectiveness happened during those years. And they produced such greats as Isaac Watts and Philip Doddridge. We can learn much from the courage and creativity of those who bucked unbiblical government mandates in order to obey God in generations past. [See Dissenting Academies in England by Irene Parker, Cambridge, U.K.: Cambridge University Press, 1914 (print on demand)]

Sometimes the church of Jesus Christ needs a crisis to get back to the basics. What might be the benefits of a governmental crack-down on Christian higher education? Potentially, we could achieve a form of education that is less generic (fulfilling broad state requirements) and is more focused on the direct application of Scripture to every aspect of life. We might get back to a system of education that is more about imparting true knowledge and skills and less about transferability, transcripts, and diplomas. We might get back to education that is a direct function of the local church– the only institution that Jesus promised to build. (Matt. 16:18)